August 14th is the feast day of St. Maximilian Kolbe, a priest whom St. John Paul II said was “the patron saint of our difficult [20th] century.” It is fitting that we remember this Franciscan priest today as well, August 15th, the Solemnity of the Assumption of Mary, as his devotion to Mary was a bedrock of his faith.

St. Maximilian Kolbe was born in 1894, baptized Rajmund Kolbe in what was then a part of Russia, but would eventually be annexed into Poland. In 1907, he and his brother Francis joined the Franciscans. He was eventually sent to Krakow to study, eventually earning two doctorate degrees. He had a brilliant mind, loved science and was fascinated by military history. Yet, he served God above all else.

Maximilian Kolbe wished to spend his vocation spreading devotion to Mary, and is credited with using the most advanced printing techniques to do so. The Immaculata Friars eventually published a daily paper with a circulation of almost a quarter million and a monthly magazine that reached over one million people. Maximilian Kolbe liked to say, “Never be afraid of loving the Blessed Virgin to much. You can never love her more than Jesus did.”

Then came World War II. Kolbe’s priestly life shifted from spreading the Gospel and devotion to the Blessed Mother on a large-scale basis to helping his fellow Poles survive. He is credited with saving the lives of at least 2000 Jews “in his friary in Niepokalanów. He was also active as a radio amateur, with Polish call letters SP3RN, vilifying Nazi activities through his reports.”

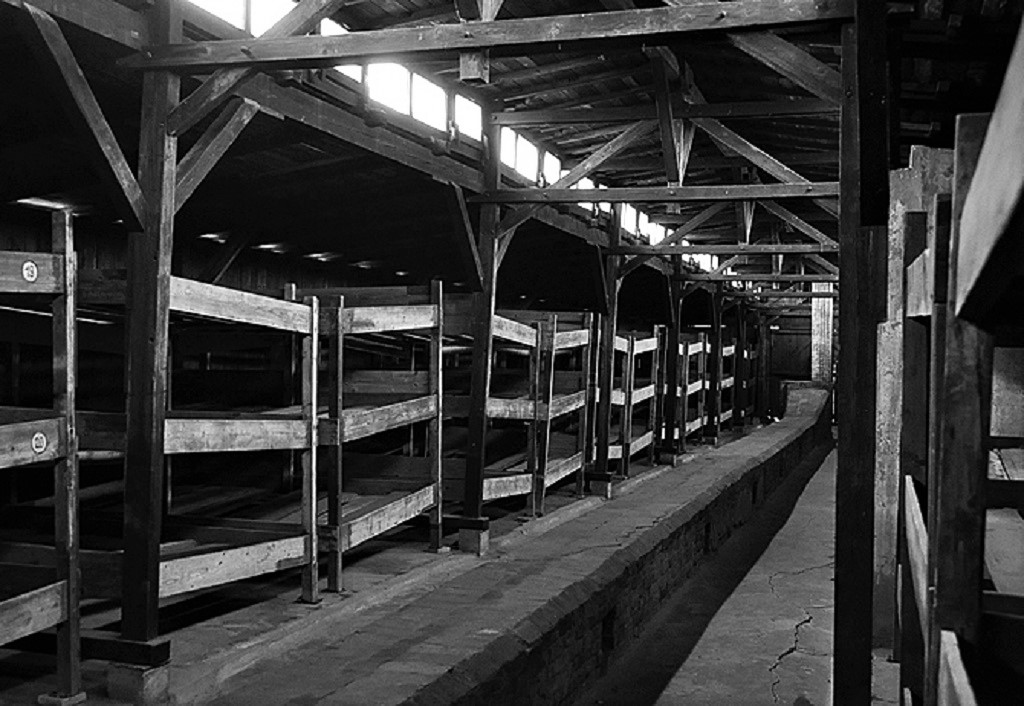

In 1941, he was arrested and sent to Auschwitz. (While the Nazis primary targets were Jews, it is said that by 1939, 80 percent of Catholic clergy in Poland had been deported to death camps. By the end of the war, six bishops, 2,020 priests, 127 seminarians, 173 lay brothers and 243 nuns were killed by the Nazis.) Fr. Kolbe spent his time in the camp working, as did the other prisoners, but also ministering to his fellow prisoners as best he could. He would often move from bed to bed at night, gently asking, “I’m a priest. Can I do anything for you?”

A prisoner later recalled how he and several others often crawled across the floor at night to be near the bed of Father Kolbe, to make their confessions and ask for consolation. Father Kolbe pleaded with his fellow prisoners to forgive their persecutors and to overcome evil with good. When he was beaten by the guards, he never cried out. Instead, he prayed for his tormentors.

In the Gospel of John, Jesus instructs His followers that they must remain in the love of God, and that love will sustain them. Then He says:

This is my commandment: love one another as I love you. No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends. (jn. 15:12-13

Few of us will ever be called to this test of faith, but Fr. Kolbe was.

In order to discourage escapes, Auschwitz had a rule that if a man escaped, ten men would be killed in retaliation. In July 1941 a man from Kolbe’s bunker escaped. The dreadful irony of the story is that the escaped prisoner was later found drowned in a camp latrine, so the terrible reprisals had been exercised without cause. But the remaining men of the bunker were led out.

The commandant Karl Fritsch screamed. ‘You will all pay for this. Ten of you will be locked in the starvation bunker without food or water until they die.’ The prisoners trembled in terror. A few days in this bunker without food and water, and a man’s intestines dried up …

The ten were selected, including Franciszek Gajowniczek, imprisoned for helping the Polish Resistance. He couldn’t help a cry of anguish. ‘My poor wife!’ he sobbed. ‘My poor children! What will they do?’ When he uttered this cry of dismay, Maximilian stepped silently forward, took off his cap, and stood before the commandant and said, ‘I am a Catholic priest. Let me take his place. I am old. He has a wife and children.’

Astounded, the icy-faced Nazi commandant asked, ‘What does this Polish pig want?’

Father Kolbe pointed with his hand to the condemned Franciszek Gajowniczek and repeated’I am a Catholic priest from Poland; I would like to take his place, because he has a wife and children.’

And so it was that Maximilian Kolbe too the place of the young Polish man with a wife and family, and was locked in a starvation bunker with others. Fr. Kolbe led the men in prayers and hymns, as one by one they slowly died. Two weeks passed. All except the priest were dead. It was decided that the bunker was needed for other things, and so the camp doctor was called in to inject the priest with carbolic acid. He died shortly thereafter.

And the man he saved, Franciszek Gajowniczek? He survived the war. He returned home to his wife, but their sons has perished. When Maximilian Kolbe was canonized in 1982 by then-Pope John Paul II, Gajowniczek was in attendance at St. Peter’s Square.

Why is St. Maximilian Kolbe so important to us today? He grew up a normal kid: he farmed and played with his brothers, helped in the shop his mother owned. He could be one of any of the millions of boys who came of age during World War II (or today for that matter.) He knew Mary wanted him as a priest for her Son, and Kolbe agreed. Then he used his talents and passions for spreading the Gospel. And when it came time for the hardest decision he ever had to make, he relied wholly on Jesus and his trust in the Blessed Mother. You can do this same this. We can. We must.