It’s not every day that we get to hear the account of the contest between Elijah and the 450 prophets of Baal. Elijah needed to show the people of Israel that the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob was the only true God. He needed more than fiery words: “‘How long will you straddle the issue? If the Lord is God, follow him; if Baal, follow him.’ The people, however, did not answer him” (1 Kings 18:21). These people didn’t care to make a decision. It took something much more dramatic: “‘You shall call on your gods, and I will call on the Lord. The God who answers with fire is God.’ All the people answered, ‘Agreed!’” (1 Kings 18:24).

It took a spectacular sacrifice and fire from heaven to get a response, and the Lord delivered. “The Lord’s fire came down and consumed the burnt offering, wood, stones, and dust, and it lapped up the water in the trench” (1 Kings 18:38). Did we hear that clearly proclaimed at Mass? “Fire came down and consumed the burnt offering, wood, stones, and dust, and it lapped up the water.” God sent fire so hot and so concentrated that it obliterated the altar of sacrifice, and instantly evaporated a trench full of water. This is much more impressive than the absentee demons of the prophets of Baal, who give no reply to the 450 men cutting themselves on their behalf.

We can hear accounts like these in the Old Testament and sit by with our popcorn, enjoying the spectacle. Surely, many of the Israelites did just that at the contest between Elijah and the prophets of Baal. But we can easily forget that these things really happened. God really sent fire from heaven at Elijah’s word. He really destroyed the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah. He really caused manna to rain down from heaven. He really allowed some of the saints to raise the dead.

God works miracles through His prophets and saints to encourage others to believe in Him. He uses these events to show us that He really exists. Although today He does not act in the same spectacular manner as He did in the Old Testament, He still performs thousands of miracles through his saints through healings, apparitions, natural disasters, and conversions.

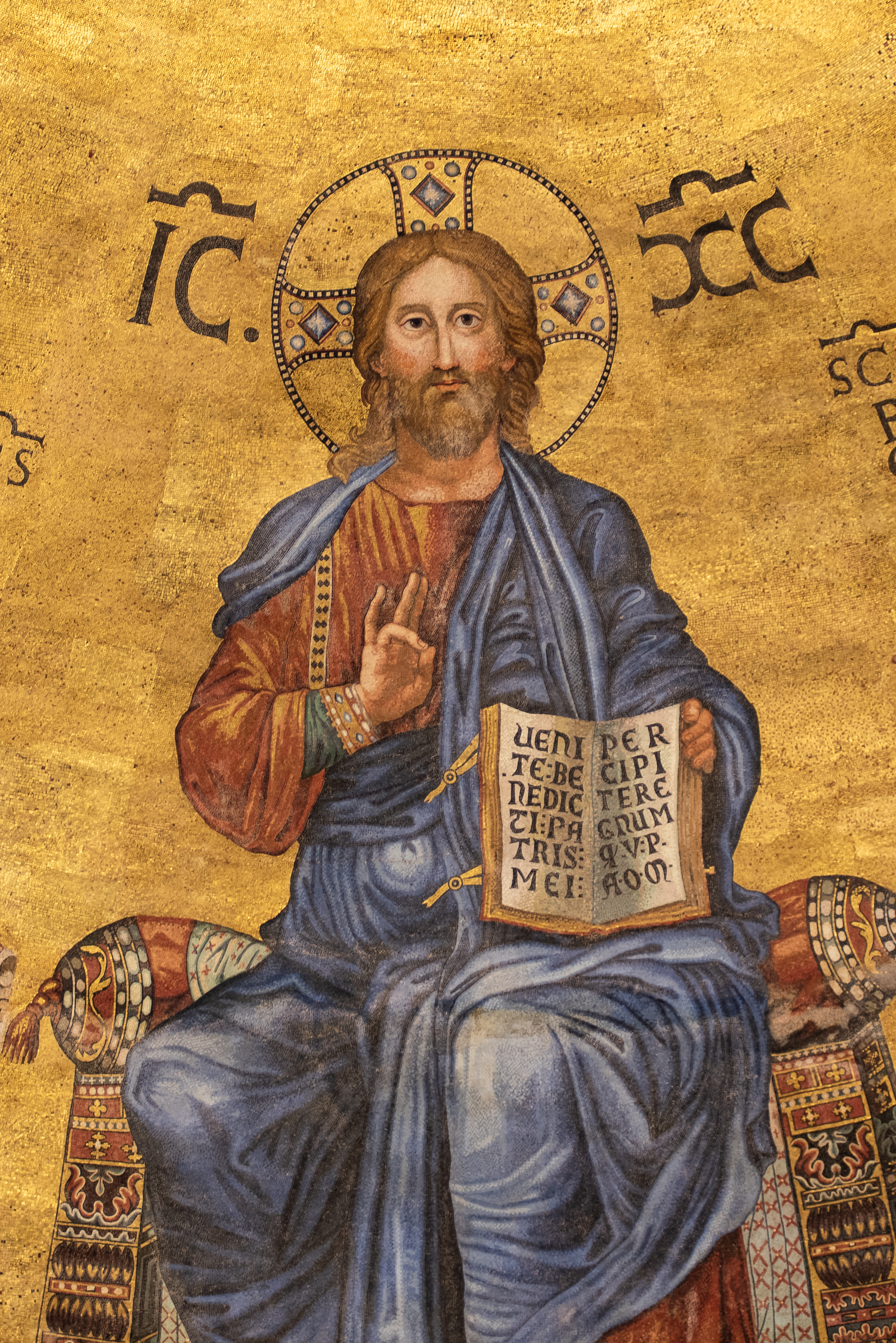

But the most significant miracle was the Incarnation. When Jesus came, He reminded us, more than any other miracle could, of the reality and closeness of God and of His claim on us. Jesus, who did not come to abolish the law or the prophets, but came “to fulfill” (Matt. 5:17), tells us in the Gospel that He is the same God who consumed the offering of Elijah. His law remains the same, and all who follow it and believe in Him will reach the kingdom of heaven. We have no excuse not to believe Him and to trust that the God who incinerates stone and takes on flesh makes commands that are not only good, but will transform us into His sons and daughters.

No todos los días escuchamos el relato de la pelea entre Elías y los 450 profetas de Baal. Elías necesitaba mostrarle al pueblo de Israel que el Dios de Abraham, Isaac y Jacob era el único Dios verdadero. Necesitaba algo más que palabras ardientes: “‘¿Hasta cuándo van a andar indecisos? Si el Señor es el verdadero Dios, síganlo; y si lo es Baal, sigan a Baal’. Pero el pueblo no supo qué responderle.” (1 Reyes 18,21). A estas personas no les importaba tomar una decisión. Fue necesario algo mucho más dramático: “‘Ustedes invocarán a su dios y yo invocaré al Señor; y el Dios que responda enviando fuego, ése es el verdadero Dios.’ Todo el pueblo respondió: ‘Está bien’”. (1 Reyes 18,24).

Fue necesario un sacrificio espectacular y fuego del cielo para obtener una respuesta, y el Señor la entregó. “Entonces bajó el fuego del Señor y consumió la víctima destinada al holocausto y la leña, y secó el agua de la zanja.” (1 Reyes 18,38). ¿Escuchamos eso claramente proclamado en la Misa? “Bajó el fuego del Señor y consumió la víctima destinada al holocausto y la leña, y secó el agua”. Dios envió fuego tan caliente y tan concentrado que destruyó el altar del sacrificio y evaporó instantáneamente una zanja llena de agua. Esto es mucho más impresionante que los demonios ausentes de los profetas de Baal, que no dan respuesta a los 450 hombres que se cortan a nombre suyo.

Podemos escuchar relatos como estos en el Antiguo Testamento y sentarnos con unas palomitas de maíz, disfrutando del espectáculo. Seguramente muchos de los israelitas hicieron precisamente eso durante la pelea entre Elías y los profetas de Baal. Pero podemos olvidar fácilmente que estas cosas realmente sucedieron. Dios realmente envió fuego del cielo ante la palabra de Elías. Realmente destruyó las ciudades de Sodoma y Gomorra. Realmente hizo que cayera maná del cielo. Realmente permitió que algunos de los santos resucitaran a los muertos.

Dios obra milagros a través de sus profetas y santos para animar a otros a creer en Él. Utiliza estos eventos para mostrarnos que realmente existe. Aunque hoy no actúa de la misma forma espectacular como en el Antiguo Testamento, todavía realiza miles de milagros a través de sus santos haciendo curaciones, apariciones, desastres naturales y conversiones.

Pero el milagro más significativo fue la Encarnación. Cuando Jesús vino, nos recordó, más que cualquier otro milagro, la realidad y la cercanía de Dios y su derecho sobre nosotros. Jesús, que no vino a abolir la ley ni a los profetas, sino que vino “a cumplir” (Mt 5,17), nos dice en el Evangelio que Él es el mismo Dios que consumió la ofrenda de Elías. Su ley sigue siendo la misma, y todo el que la sigue y cree en Él alcanzará el reino de los cielos. No tenemos excusa para no creerle y confiar en que el Dios que incinera piedra y toma carne, da mandatos que no sólo son buenos, sino que nos transformarán en sus hijos e hijas.

David Dashiell is a freelance author and editor in Nashville, Tennessee. He has a master’s degree in theology from Franciscan University, and is the editor of the anthology Ever Ancient, Ever New: Why Younger Generations Are Embracing Traditional Catholicism.

David Dashiell is a freelance author and editor in Nashville, Tennessee. He has a master’s degree in theology from Franciscan University, and is the editor of the anthology Ever Ancient, Ever New: Why Younger Generations Are Embracing Traditional Catholicism.

Feature Image Credit: José De La Cruz, cathopic.com/photo/7750-burn-my-being