When Jesus came down from the mountain, great crowds followed him. And then a leper approached, did him homage, and said, “Lord, if you wish, you can make me clean.” He stretched out his hand, touched him, and said, “I will do it. Be made clean.” His leprosy was cleansed immediately. (Mt. 8:1-3)

Leprosy (now known as Hansen’s disease) was a feared illness in both the ancient and modern worlds. If often disfigures its victims and was thought to be highly contagious; those with leprosy were made to live apart from a town or village and often made to ring a bell and call out, “Unclean! Unclean!” so that others would stay away. They relied on begging.

(We know now that leprosy is not contagious via skin contact, and is relatively hard to contract. It is a bacterial infection and can be cured.)

Today is the feast of St. Damien of Molokai. He was a Belgian priest, born in 1840, who volunteered to care for the lepers on the island of Molokai. These men and women had literally been exiled to this island, as far away from polite society as possible. Many of these people were Catholic, and begged for the care of a priest, but no would volunteer … until Damien. It was assumed by all that he was essentially accepting a death sentence.

The leper colony on Molokai was established in 1866 and officially closed in 1969 (although some lepers and their descendants choose to live there.) While we tend to think of Molokai as a lush vacation paradise, the conditions of the colony were beyond harsh.

The area was void of all amenities. No buildings, shelters nor potable water were available. These first arrivals dwelled in rock enclosures, caves, and in the most rudimentary shacks, built of sticks and dried leaves…

Oral histories recall some of the horrors: the leprosy victims, arriving by ship, were sometimes told to jump overboard and swim for their lives. Occasionally a strong rope was run from the anchored ship to the shore, and they pulled themselves painfully through the high, salty waves, with legs and feet dangling below like bait on a fishing line.

The ship’s crew would then throw into the water whatever supplies had been sent, relying on currents to carry them ashore or the exiles swimming to retrieve them.

The men, women and children exiled to Molokai were torn from their families and thrust into this harsh environment. Clothing became scarce, as was food.

The island had become a wasteland in human terms, despite its natural beauty. The leprosy victims of Molokai faced hopeless conditions and extreme deprivation, sometimes lacking not only basic palliative care but even the means of survival.

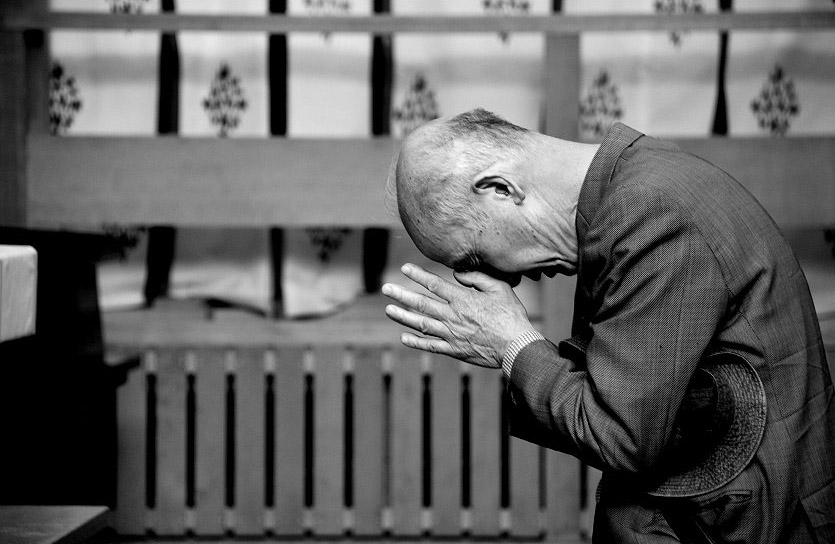

Damien set about trying to normalize life for the people of Molokai. He became their advocate with the caretakers (who were often cruel), worked to build homes, a church, gardens for both food and beauty. As a farm boy, Damien knew how to work. He also ministered to people, celebrating Mass, hearing confessions, baptizing and marrying people. He also strongly believed that beauty and art was necessary for the souls of the people in Molokai; he established choirs and musical ensembles. Those that knew him remembered him as a tireless worker, often to the point of exhaustion.

Damien did eventually contract leprosy and died during Holy Week of 1889. He was canonized by Pope Benedict XVI in 2009.

St. Damien’s life is truly one of a saint: he reflected and exemplified the life of Jesus. He brought the Good News to a people who were without hope. He brought them faith, hope, love. He taught them that they were worthy of a life of dignity, just as any child of God is so worthy. St. Damien chose to leave his life behind and live the life that Christ chose for him. He chose to embrace Christ, and in doing so, embraced the leper.

[Photo: Public domain. Father Damien with the Kalawao Girls’ Choir, circa 1870]